In the second section of Rebecca Millers captivating five parts documentary on Martin ScorseseThe chronological review of his life and career reaches the classic “taxi driver in 1976.” Jodie Foster, who is for a new interview on a movie she has been discussing for almost five decades, talks about how “Gleful” her director would make films. “He was excited about how the blood was made,” Foster says and her eyes broadened to mimic Scorsese’s joy. “And when he was going to blow off the guy, how they put small pieces of styrofoam in the blood so it would attach to the wall and stay there.”

“We had a fantastic time,” says Scorsese. But then he swings. He starts talking about how the studio “got very angry with us because of violence“Due to the language because of the” disturbing “depiction of New York City’s” good looking “Underbelly. When MPAA beat” Taxi driver “with an X-rating, the Columbia pictures Scorsese said to edit it to an R-rating or they would.

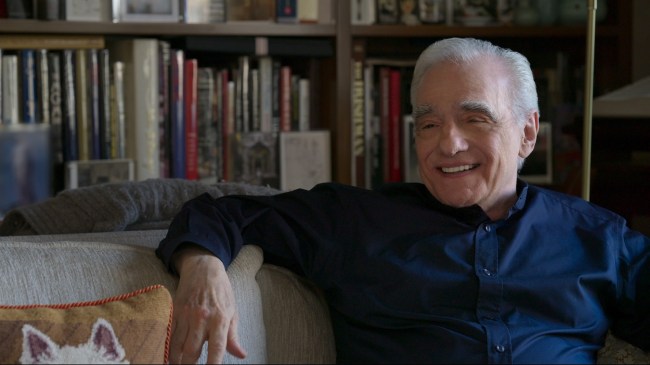

“That’s when I dropped it,” says Scorsese. Miller moves in to ask what he did, exactly, and scorsese – visibly annoyed by memory – repeats himself, stems a bit and then breaks into a wide grin. He knows the story from there, but the documentary allows Steven Spielberg (whom Scorsese demanded advice at that time) and Brian de Palma (who remembers that Scorsese “went crazy”) to set what happens next. Everything Scorsese must explain is if he had a gun (he says he didn’t) and why he “would get one.” “I would go in, find out where the rough cut is, break the windows and remove it,” he says. “They would ruin the movie anyway, you know? So let me ruin it.”

Thankfully, it never came to it, but the director’s two extremes-the divine Joy Scorsese finds by making films set against the almost total ruin that he has endured for his art rest in the middle of what Miller appropriately appoints “a movie portrait.” While Touching Upon All His Feature Movies (Almost), Including New Interviews From Famous Collaborators Like Robert De Nir and Leonardo DiCaprio, as well as Childhood Friends and Family Members (including Of Cinema’s True “Cornerstones” (as Spielberg calls heaven) In order to better appreciate how he’s interrogated them, year after year, right in front of our eyes.

Still, as heavy as “Mr. Scorsese” can get – to deal with the modern US torment of Travis Bickles, the emergence of religious law (timed to “The Last Temptation of Christ”), and Scorses’s brush with death, four divorces and seizures with depression – it is also enormously entertaining. Miller launches straight into his refreshing assessment and keeps the pace up.

The first hour is largely biographical and covers Scorsese’s early days in New York from childhood to film school. Archiving interviews with their parents (many of whom come from Scorsese’s own documentary from 1974, “Italian American”) help to contextualize Scorsese’s own sincere memories.

“I saw serious things,” he says before a pointed break. “Violence was imminent all the time.”

Miller also has some of Scorsese’s childhood friends who, in addition to the usual one-on-one interviews, collect around a bar room table to remind you of Scorsese and later De Niro. They remember their lower East Side Quarter as “the hub of the five mafia families” and share a rioting story about finding a dead body which means that such observations were not so unusual.

Scorsese clearly experienced a lot from first and foremost, but his asthma also held him in his room for extended periods, where he looked at the neighborhood’s drama play from window windows to window windows, as screenwriter Mitch Pileggi suggests, founded him to see the world through film frames. (Scorsese credits the formative vantage point for why he loves high angle images, while Spike Lee Pops in to say, on behalf of all cinephiles, “thank God for asthma!”)

After recognizing the impact Catholicism Had on a young scorsese (who never completely left him) and travels out west for his first days in LA (which never really fits), the premiere ends with taking up “Mean Streets” – with an irresistible kicker of a smirking de Niro – and the series shifts into a Film-by-movie narrative structure. As he worked through his Oeuvre, thematic overlap and stylistic progression (with remarkable assists from the legendary editor Thelma Schoonmaker, drives her editing Bay, and animated renders of Scorse’s first hand -drawn storyboards), Miller, in particular Miller.

She takes in the real inspiration for De Niro Johnny Boy to answer questions about the character. (He does not disappoint.) She gives her husband, Daniel Day-Lewis, to link “The Age of Innocence” to the rest of Scorsese’s movies by quoting “Savagery of it.” And when scorsese admits “there were some drugs on” during the production at “New York, New York,” Paul Schrader provides a blunt, more colorful description: “These were the cocaine years,” he says, “(and) ‘New York, New York’ was a very coke-ya set.”

Isabella Rossellini earns a similar feature when she clarifies her ex-spouse Near death experience 1978 and his destructive mood in the years after. “He could demolish a room,” says Rossellini. She remembers mornings that he would wake up angry and mumble “fuck it, fuck it”, over and over again, without explanation, but she also realized that he would channel the anger for his work. “(It) gave him endurance” to get through shots, she says, shortly before Scorsese credits therapy to save his life. “If it wasn’t for the doctor – five days a week, phone calls on the weekend, strongly steady work on straightening out my head – I would be dead.”

The director’s dedicated and film researchers in general may recognize materials that are covered by Miller’s five -hour documentary. Fans of some films may also be disappointed with the time assigned to each of them (especially if you love “Hugo”, the only feature that does not get any dissection), and it is a bit annoying that an episodic series (which is nicely divided into episodic arches) chooses to exclude all scorsese’s’s TV work. (No “Boardwalk Empire”, no “pretending it’s a city” and – least surprisingly – no “Vinyl.”)

But “Mr. Scorsese” entertainment value is without a doubt. Where else can you hear about Scorsese who throws a desk out through a window on the set “Gangs of New York” during a fight with Harvey Weinstein? Or shoemakers who remember how Scorsese would direct her own mother in movies? (“He would literally just say,” Ok, mom, start now ” – give her the first line and then ask her to improvise the rest.) Or a clearly uncomfortable DiCaprio that says the words” Woman’s buttocks “while breaking down the opening shot by” The Wolf of Wall Street “?

Nor could anyone reject the value of Miller’s analysis. From the opening song (“Sympathy for the Devil”, of course) who plays under a montage of existential issues relied on by his films to the closing message as Scorsese literally Living for filmmaking (Although it kills him), “Mr. Scorsese” confronts her subject’s lifelong dichotomies while defining how each of his films helps to unite and define them.

To close his introductory date, says a TV host to Scorsese, “you once said,” I’m a gangster, and I’m a priest. “” Replies Scorsese, “I told Gore Vidal one day,” There is only one of two things you can be in my neighborhood. You can either be a priest or a gangster. “And (vidal) said, ‘And you both became.’ ‘

To paraphrase Spike Lee, thank God he did. Thankfully he could. And thankfully, he found so many ways to share himself with the world.

Rating: A-

“Mr. Scorsese” premiered on Saturday, October 4 at the New York Film Festival. Apple releases all five episodes on Friday 17 October.