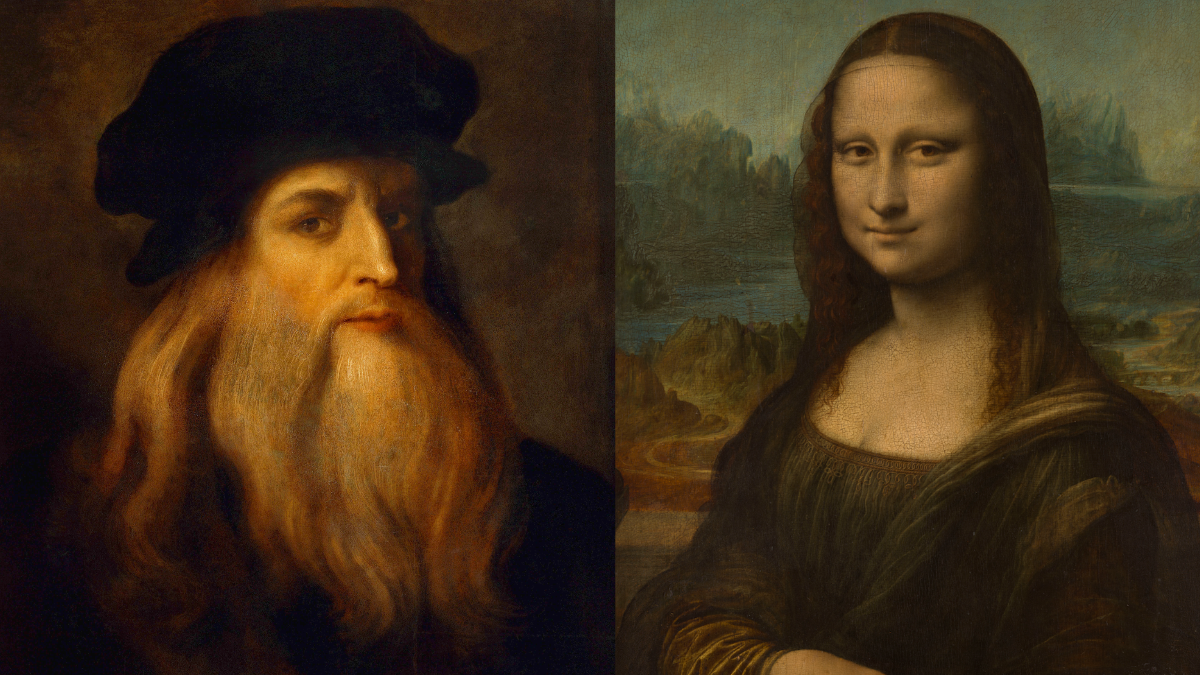

“It’s been wonderful to get the old dog to learn some new tricks,” said Ken Burns, now in his fifth decade as a filmmaker and talked about his first non-American documentary subject. It is also the longest back in history that Burns has ever stretched for one of his films, although the subject is uniquely modern. “Leonardo da Vinci” (PBS) is a four-hour journey into the idea of perhaps the most curious man who ever lived-renaissance-era engineer, theorist, sculptor, researcher, anatomist and artist responsible for the most famous painting of all time.

The two -part series was collaborated by Sarah Burns and David McMahon (Burn’s daughter and son -in -law), who moved with his children to Florence, Italy, while writing and researched the documentary. The project is produced with precision and a genuine emotional sweep and also has shared screens, dynamic cinematography and unexpected contributors on the camera (including a cardiac surgeon and an Oscar-winning filmmaker), which marks an inventive new chapter in Ken Burns Canon.

“Leonardo“ Signals a departure for you when it comes to the subject, but how do you think he is still in a continuum with your second work?

Ken Burns Nature’s Primat has been a huge ongoing theme in the movies, including in “The American Buffalo” and “the national parks.” Or as Leonardo can say, the lack of people to see ourselves and our potential are reflected in nature. The central idea of Leonardo is how he dreamed of the rest of us, which has also been a big theme. He had no microscope and no telescope, and yet you feel that he understood that there is a deep similarity between the architecture of the atom and the architecture of the solar system. He actually did not know what we do now, but he predicted that feeling of natural union truth in the world.

He was born in 1452, but the documentary gives us a sense of the times he lived in and how exciting it must have been to see his work.

David McMahon When he showed cartoon in his “Virgin and Child with Saint Anne” About 1502, the word was spread as crazy about him. People said, “This guy is doing extraordinary things and you have to rush to see it.” It was one of these transformative times.

Ken Burns It is interesting, I remember being 24 in 1977 at Ziegfeld, the largest theater in New York, and looked at the premiere of “Star Wars.” And when they went in Hyperspace, 2,000 people stood up and screamed their heads. And there is a way in which Leonardo reminds me of “Millennium Falcon” Goes to light-speed-the energy and groundbreaking tension and creativity.

For movie lovers, the participation of Guillermo del Toro is also special. He is the first modern voice we hear and speaks poetically about the relationship between knowledge and imagination. How did he get involved?

Sarah Burns It was a little serendipity. We knew we would have art historians and cinemas, but we are always looking for different perspectives on our subjects. I came across some pictures of Guillermo’s notebooks, and how he integrates sketches of mythical creatures and monsters along with text on the page reminded me of Leonardo. So we handed out via E -post to get in touch with him at Zoom.

Ken Burns We came to Zoom and Guillermo just went by Leonardo. So not even five minutes in, I said, “Guillermo, hold on, we bring a camera herd to you.” It was fantastic. He gets the idea that Leonardo’s mission, his sacred duty, was to interrogate the universe. And you see in Guillermo the same restless quality and the same unbroken joy. He just can’t sit still. When the series was over, he said he had to go because he flies to Japan with JJ Abrams to buy toys.

The documentary uses plenty of shared screens, where we see Leonardo’s sketches of Manpowered Flight next to pictures of birds, for example. How did you develop that style?

McMahon Our goal was to put everyone between Leonardo’s ears. And our pole star was his notebook drawings, which are best understood in many cases if you see them together with the world as he observed it. By putting these things side by side you understand his thinking better and the mathematical relationships he saw among things. We were not going to discover new facts about his life – people have tried to do it – but instead, with the shared screens, with our cinematography, we could get people closer to Leonardo in a more ecstatic way.

The project deals with the strong consensus that Leonardo was a gay man, even if you present what is known about his personal life without turning it into a tabloid subject.

Ken Burns Yes, it’s just a fact. Maybe some people have a desire to do more of a drama of their sexuality or to make it more furry or scanning. But Leonardo constantly tells me that nothing is binary, everything is fluid.

McMahon Of course, we did not sensationalized his sexuality, and Florence at that time was a place where you didn’t have to be particularly concerned if you were gay. It happened to me that Bodegas in Florence during Leonardo’s time was like Warhol’s factory. You can imagine that all these young artists spend time with each other. And the leisure activities or the chosen drugs may have been different, but the youthful energy and hunger could have been very much the same.

The documentary clims with “Mona Lisa”, which is depicted as a fantastic crescendo of his life’s work. It seems that the whole story was designed to land at that place.

Sarah Burns Yes, it felt like “Mona Lisa” was the most challenging of the paintings to tell the story. Many people have a feeling that it is overestimated – you go to see it on the Louvre, there are a million people who take selfies, and it is not necessarily the best way to experience a work of art. And so keeping it to the end, we hoped that it could be better as a beautiful culmination of all his scientific exploration, all his sketch and painting and the study he had done throughout his life.

Ken Burns I hope people don’t joke more about her smile anymore. (Laugh) It’s an easy way to turn off curiosity. It is a way to arm her length, when she is like the key to the universe. You know, right there in her eyes, in her hair, in her neck and in the background, in all these things is a roseta stone of human existence. That’s what Leonardo gave us.

This story originally ran in the race begins the edition of Thewraps Awards Magazine. Read more from the question here.