Broadly speaking, there are two obvious ways to make a documentary about the dangers—and the damage already done—of the stand-your-ground laws that Florida has been popularized since the adoption of its own version in 2005.

The first would be a top-down, macro-political strategy that examined the pitfalls of applying the castle doctrine to a racially stratified country with more guns than people. It would start with the fact that homicides have increased eight percent in states where citizens have no obligation to retreat before using deadly force in response to a perceived threat to their lives, and from there it would isolate a variety of examples for to illustrate that 70 percent of the people killed in Florida’s stand-alone cases have been unarmed. That 79 percent of their killers could has retreated safely. That white-on-black murders are five times more likely to be considered “justifiable” than the other way around. (Data taken from Rockefeller Institute of Government.) One such film would offer a sober—if largely analytical—reminder of what its self-selecting audience already suspected about these laws.

It would be an understatement to say that Geeta Gandbhir “The perfect neighbor” takes Other approach, just as it would be an understatement to say the film takes that approach to jarring extremes. Gandbhir’s unforgettable documentary, shot almost entirely by police cameras and interrogation room CCTV, crystallizes the horrors of stand-alone laws by examining their effects through the lens of a single case – one that poignantly illustrates the flaws in castle doctrines (among other policies). failures) by painting a microcosmic portrait of white America’s inability to interpret between fear and anger.

Specific laws aren’t even mentioned by name until the film is more than halfway through, as Gandbhir chooses to work the issue from the inside out, with the you-are-there reality of the films she uses to get viewers right. into the heart of what is ultimately a human issue. Indeed, a subjective camera has rarely been more damning than it is here—here, in an American Horror Story that doesn’t depend on whether or not Susan Lorincz was actually in danger when she fired at the unarmed neighbor who knocked on her front door, but rather whether Susan Lorincz thought she was in danger when the young black mother from across the street came to collect her son’s confiscated tablet.

In a country where the most powerful group of people have been made to feel permanently insecure, everyone else has good reason to fear for their lives. And that fear is only further legitimized by laws that allow fear itself to be a credible excuse for murder. Everyone in Lorincz’s quiet Ocala neighborhood knew she was afraid of the world outside her door, but they didn’t realize how afraid they should have been in return. Most of them thought only of the 60-year-old doctor – a doctor of what? — as a local nuisance. The children who played soccer on the communal grass field in front of her house called her a “Karen”, to which Lorincz often responded by calling the police.

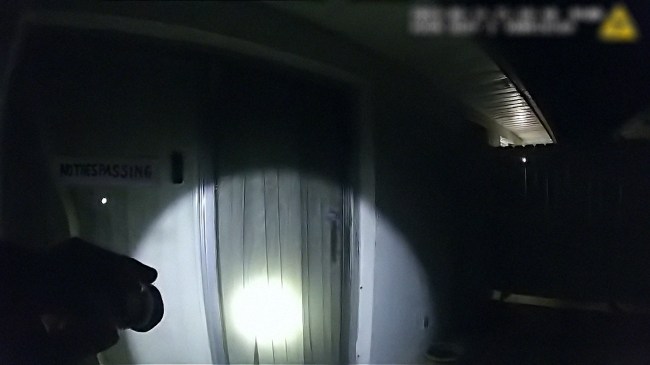

That so much of the film’s background can be drawn from police body camera The videos are proof of how often Lorincz harassed the authorities. She was upset by the sound of young people having fun on lazy summer afternoons, and while viewers will understandably brace themselves for the police to side with the annoyed white lady over the group of high-spirited black kids, it only takes a few audio complaints to the police to identify Lorincz as “a psycho.”

Perhaps the authorities would have taken more aggressive measures if the shoe was on the other foot. Perhaps the police had asked if she owned a weapon after it emerged that she had experienced violent panic attacks as a result of her sexual trauma. Maybe the people across the street would have been more wary if it weren’t so common for the Susan Lorinczs of the world to call little kids the n-word just for playing too close to her truck.

Ajike Owens radiates exquisite elegance and laughs off the cops the first time we see them question the mother of four about the woman across the street. Yes, she threw Lorincz’s “no trespassing” sign in her neighbor’s general direction (Lorincz reacts like it was attempted murder), but the sign wasn’t even on Lorincz’s property to begin with. She knew that Lorincz was in no real danger from her or her children or from anyone else on their street, and she assumed that—despite the neighbor’s racist screams—the opposite was pretty much true as well. But Lorincz didn’t see things the same way in her confused mind, and on the night of June 2, 2023, she killed Owens for the crime of knocking on her front door.

We see the news of Owen’s death spread through her community in body camera footage recorded by the police arriving on the scene; the immediate fallout from this eminently preventable tragedy is filtered through the same legal apparatus that allowed it to happen in the first place. The camera is at once both objective and subjective — coldly unblinking but oriented entirely around human attention and movement.

The callous indifference encoded in the body cam aesthetic collides with the intimate proximity of watching an officer tell the father of Owen’s child that she’s gone, and then listening (from just inches away) as the man relays that message to his newly motherless child . The disparity between what the law allows from some and deprives others has rarely been as devastating as here. “Are you hurt?”, a police officer asks one of Owen’s sons. “No,” he cries, “but my heart is broken.”

“The Perfect Neighbor” veers from heartbreak to absurdity — and the outrage that comes with it — as it shifts to focus on the aftermath of the murder, Gandbhir’s perspective widening from body cameras to the surveillance footage captured in the interrogation room of the Ocala police station. It is terrifying to see Lorincz sitting in horror at what she has done; to see her exaggerate the threat presented by Owens, downplay the vitriol of her own racism, and grossly misinterpret the timeline of events leading up to the murder. It’s even more chilling to see the detectives let her go free later that night, even though we understand her case has only just begun.

To some extent, Lorincz’s case is too specific to serve as a perfect synecdoche for the 79 percent of Florida’s stand-alone murders in which the attacker could have safely retreated. The situation had been going on for months on end and Lorincz was clearly suffering from a form of PTSD. But therein lies the power of Gandbhir’s decision to examine stand-alone laws through a pinhole: each crime has its own mess of extenuating circumstances, but all feel justified in the heat of the moment. To encourage citizens to be the combative arbiters of their own reality is to weaponize – all too literally – the most dangerous prejudices they promote on a daily basis. It’s bad enough that we allow the police to do that, but it might be even worse to give that power to someone who likes to see himself as the perfect neighbor.

Grade: B+

“The Perfect Neighbor” premiered in 2025 Sundance Film festival. It is currently seeking distribution in the United States.

Want to keep you updated on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, where our chief film critic and chief reviews editor gathers the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings—all available only to subscribers.